SAVOIR-FAIRE

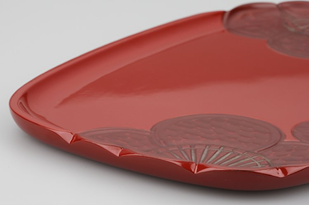

TAKAOKA SHIKKI (TAKAOKA LACQERWARE)

LAQUERWARE / - Takaoka, TOYAMA

Takaoka lacquerware appeared in the early 17th century, during the first half of the Edo period (1603-1868), after Toshinaga Maeda, lord of the Kaga estate, built the Takaoka castle and established the town of Takaoka. Craftsmen and merchants from all over the country flocked there and started to make armor pieces and various everyday objects such as furniture, dishes, etc. The lacquerware called "akamono", characterized by its dark reddish-brown color, is widely known, and was sold not only in the vicinity of Takaoka, but also all over northern Japan, as far as Hokkaido. In addition, from the end of the era to the Meiji era, many talented master craftsmen appeared and various techniques such as raden inlaying and sabi-ire (patina) were created in the area, giving Takaoka its status as a lacquer producing region. Takaoka lacquerware was designated as a national "Traditional Craft" in 1975.

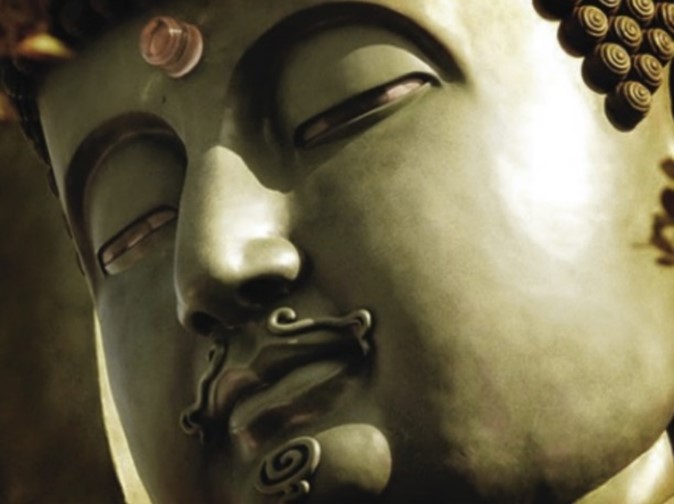

TAKAOKA DOKI (TAKAOKA COPPERWARE)

METAL WORKS - Takaoka, TOYAMA

The history of Takaoka copper or "Takaoka-dôki" begins in 1611 when Toshinaga Maeda, the second feudal lord of Kaga, called upon seven highly skilled metal smelters from all over Japan to ensure the prosperity of the city. The smithy district where this craft was born still exists today and has kept its name of "Kanayamachi". "Takaoka-dôki" is a generic term for all metal products made in the city of Takaoka, Toyama prefecture. Contrary to what the name might suggest, which refers only to "copper (dôki)", these items are also made from materials such as aluminum alloys, tin, iron, gold and silver, in addition to copper alloys such as bronze and brass. Using a variety of ironworking, casting, forging and other techniques that are recognized throughout the country, craftsmen are able to make both large objects such as Buddhist statues and bells, as well as smaller pieces such as "orin" singing bowls and bronze statues. Today, Takaoka produces 95% of Japan's copper objects. Takaoka copper work was designated as a national "Traditional Craft" in 1975.

KOISHIWARA YAKI (KOISHIWARA WARE)

CERAMIC - Toho, FUKUOKA

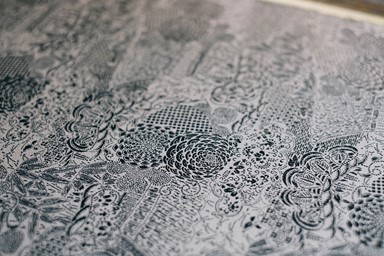

Koishiwara ceramics, or "Koishiwara-yaki", is a generic name for pottery fired in the village of Tôhô, Asakura District, Fukuoka Prefecture. It appeared in 1662, when Mitsuyuki Kuroka, the third feudal lord of Fukuoka, invited a potter from Imari, Hizen Province, to open a kiln. This style of ceramics is characterized by unique geometric patterns engraved with regularity by the use of the tip of a blade, or a brush, while turning the piece on a potter's wheel. Among the techniques used are the use of brushes, the "tobi kanna", a kind of plane whose regular rebound on the surface of the ceramic moving in the potter's wheel traces a series of discontinuous incisions that form a geometric pattern, the work with a comb, the "nagashi-kake", which consists in pouring the glaze directly on the piece, or "uchi-kake", glazing by projections, etc. In 1954, the writer Soetsu Yanagi and the ceramist Bernard Leach visited Koishiwara and declared, not without admiration, that they had found there "the height of functional beauty", thus contributing to the national recognition of this place. In 1958, Koishiwara ceramics won the Grand Prix at the World's Fair in Brussels and gained international recognition. Koishiwara ceramics was designated as a national "Traditional Craft" in 1975.

KABA ZAIKU (KABA CHERRYBARK WOODCRAFT)

WOOD CRAFTS – Kakunodate, AKITA

Kabazaiku, the traditional craft of working mountain cherry bark to cover or shape various objects, has developed exclusively in the city of Kakunodate, Akita Prefecture. Frosted bark" is the finish that restores the appearance of raw bark, and "glossy" or "unadorned bark" is the finish where the surface is finely sanded to a glazed effect. Everyday objects, such as tea caddies, become more lustrous as they are handled day by day, and retain the shine of mountain cherry trees. The history of Kabazaiku begins in the late 18th century, and its tradition is said to date back more than 200 years. Traditional Kabazaiku was generally used for making small objects - which is still the case today, as evidenced by the many tea and tobacco boxes made using this technique. The bark of the cherry tree has very interesting natural properties for preservation; in fact, a box made entirely with the Kabazaiku technique keeps the dried elements (tea, tobacco, medicinal herbs) stored in it at a constant level of humidity and protects them from external changes. Kabazaiku objects are usually dark red in color due to the original color of the bark and the animal glue used. Kabazaiku was designated as a national "Traditional Craft" in 1976.

ODATE MAGE-WAPPA (ODATE BENTWOOD)

WOOD CRAFTS – Odate, AKITA

Magewappa craft dates back to the Edo period (1603-1868), and refers to the manufacture of cylindrical or curved objects (boxes, dishes, containers etc.) made entirely from the raw wood of Akita Prefecture cedars. Because of the sweet woody scent of Akita cedar, the beauty of its veins, and because it enhances the flavor and quality of ingredients, this craft is mainly used to make tableware, various containers, trays, and bento (lunch basket) boxes. The ability to make cylindrical or curved objects from Akita cedar wood has existed for nearly 1300 years, but production really developed as an economic activity in the second half of the 17th century. Indeed, the western branch of the Satake family, then lord of Ôdate, encouraged, at this period, the warriors of lower status to make this craft a secondary activity, thus contributing to its development. Later, with the generalization of plastic products, the activity related to the Magewappa handicraft temporarily experienced a period of decline, but because of the beauty of the veins of the cedar wood used in this handicraft, and being a simple natural material, in accordance with the recent sensitivities and in the perspective of post-industrialization, we observe a revaluation of this last one, with the manufacture of many products adapted to our contemporary ways of life. In 1980, Magewappa was designated as the only national traditional craft in this field.

BIRUDAN WASHI(BIRUDAN TRADITIONAL JAPANESE PAPER)

TRADITIONAL JAPANESE PAPER – Tateyama, TOYAMA

Japanese traditional paper Birudan, or "Birudan Washi" is one of the types of traditional paper grouped under the name "Etchu Washi", designated as a National Traditional Craft in 1988. The history of Etchu Washi paper dates back to the Nara period (710-794). At that time, it was widely used for copying sutras, and it flourished especially in the Edo period (1603-1868). Birudan Washi has been popular and used in daily life for a long time, and has gained an excellent reputation for its strength and flexibility. However, the handmade production of Birudan Washi has declined with the rise of mechanically produced paper, and today there is only one Birudan Washi maker left. Takakuni Kawahara is the sole heir of this know-how and continues to make Birudan Washi according to traditional methods in his workshop Kawahara Seisakusyo. Takakuni Kawahara is also distinguished by the fact that he grows the plants used as raw materials for the paper himself, from the "Tororo Aoi" (a variety of hibiscus), whose roots are used as a dispersing agent, to the famous "Kôzo" (paper mulberry) used for its fibers. In this way, Mr. Kawahara is able to respond to any type of order.

YAMANAKA SIKKI(YAMANAKA LACQUERWARE)

LACQUERWARE – Kaga, ISHIKAWA

Yamanaka lacquerware is produced in Yamanaka Onsen District, Kaga City, Ishikawa Prefecture. The special feature of Yamanaka lacquerware is the technique used to carve the wood on a lathe, which enhances the natural texture of the wood grain and the refined beauty of the "maki-e" work - a decoration method that consists of sprinkling the lacquer with gold or silver powder. The history of this craft dates back to the second half of the 16th century, when a group of craftsmen from other regions settled in a village upstream of Yamanaka Onsen, Kaga City, to seek quality materials. It is said that the technique began to take hold in the vicinity of Yamanaka Onsen when these craftsmen were able to make a living from their work with wood lathe engraving. In addition, during the first half of the 19th century, when methods of coating wood with lacquer and the work of "maki-e" were imported into the area from Kyoto, Aizu and Kanazawa, the original Yamanaka technique was developed. This technique combines a very characteristic work of wood, which is then lacquered and decorated with maki-e. The result is elegant and elaborately decorated pieces whose artistic value is widely recognized. Yamanaka lacquerware was designated as a national "Traditional Craft" in 1975.

ÔZU WASHI(ÔZU TRADITIONAL JAPANESE PAPER)

TRADITIONAL JAPANESE PAPER – Uchiko, EHIME

Traditional Japanese Washi paper is a traditional Japanese paper made by hand in Uchiko, Ôzu City, Ehime Prefecture. Paper was already made in Ôzu during the Heian period (794-1185), but it was in the middle of the Edo period (1603-1868) that Ôzu Washi as we know it today began to be made. It is often used as calligraphy paper, shôji (sliding wall) paper, framing paper and wrapping paper. Being a thin paper with few irregularities, it is particularly easy to handle and its high quality is highly appreciated in calligraphy. At the end of the Meiji era, there were still 430 traditional paper mills, but by the end of the war, with the advent of machines, the number had dropped to 74. Today, there are only two craftsmen left in the town, but one of them, Hiroyuki Saitô, manager of Ikazaki Shachû workshop, is studying European gilding techniques and exploring new possibilities around Japanese paper. Ôzu Washi paper was designated as a national "Traditional Craft" in 1977.

BIZEN YAKI (BIZEN WARE)

CERAMIC – BIZEN, OKAYAMA

Bizen ceramics, or "Bizen-yaki", refers to the pottery made in the vicinity of Bizen City, Okayama Prefecture. Bizen ceramics is one of the so-called Six Ancestral Kilns of Japan. Since the activity was particularly prosperous in the district of Imbe, Bizen city, this type of ceramics is also known as "Imbe-yaki". In the district in question, one can see, dominating the landscape, the numerous rectangular brick chimneys which come from the Bizen kilns. Bizen ceramics have several unique characteristics: they are made one by one from local clay rich in red iron and of high quality, they are fired without using glaze ("yakishime"), and the various patterns are due to "kiln effects" (flames, ash splashes, etc., depending on the arrangement of the pieces in the kiln during firing). Nowadays, many pieces for tea service, sake service, plates, etc. are produced. It is said that "the more one uses these ceramics, the more their character asserts itself"; and one never tires of their sober beauty, without eccentricity. Even abroad, the pure Japanese charm of Bizen ceramics is not uncommon. Finally, one of the other characteristics of this craft is that it has produced many master craftsmen who have been designated as living national treasures. Bizen ceramics as such was designated as a national "Traditional Craft" in 1977.

TOKYO SOME KOMON (TOKYO FINE PATTERNED DYEING)

DYED TEXTILES – Shinjuku, TOKYO

"Some Komon" refers to a style of stencil dyeing that developed during the Edo period. This technique is said to have originated from a practice dating back to the 8th century of applying dye-coated wooden stencils to fabrics to imprint patterns on them. Later, in the 13th century, it became a dyeing technique for clothes. Tokyo Some Komon" dyeing is characterized by the use of a single, refined color and geometric patterns that are so intricate that they appear plain when viewed from a distance, and reveal their complexity and finesse when approached. Kyoto was the center of kimono culture, but as the population grew in Edo (now Tokyo), the craftsmen moved from Kyoto to Edo. Since dyeing requires large amounts of water, the majority of craftsmen settled near the Kandagawa River where access to clean and abundant water was assured, and these areas became dyeing centers. Even today, remnants of the old workshops remain in these areas. In 1976, "Tokyo Some Komon" dyeing was designated as a national "Traditional Craft".

OSAKA RANMA (OSAKA CARVED WOODEN PANEL)

WOOD CRAFTS – Osaka/Kishiwada/Suita, OSAKA

Osaka carved wooden panel (called Osaka Ranma in Japanese) is a type of Ranma produced in the Osaka area. Ranma is a wooden panel installed between the ceiling and lintels in adjacent rooms or between rooms and corridors in Japanese style houses. Its origins date back to around the beginning of the 17th century. In the early days, it was for the privileged class and Kyoto was the center of manufacturing, but in the mid-Edo period, it began to be incorporated into the dwellings of ordinary people, and the center of manufacturing moved to Osaka. Osaka ranma are characterized by a variety of styles, including carved and openwork ones. In 1975, Osaka Ranma was designated as a national traditional craft.

NAGISO ROKURO ZAIKU (NAGISO WOODTURNING)

WOOD CRAFTS – Nagiso, NAGANO

Nagiso Rokuro Zaiku are completely handmade woodwork items made in the area around Nagiso Town, Kiso-gun, Nagano Prefecture. This traditional craft, which originated in the first half of the 18th century, is known for a special woodworking technique called "rokuro-zaiku," in which round pieces of wood are shaved with a plane while being spun on a potter's wheel to make white wooden products. It requires a high level of skill and knowledge of the properties of the wood, and is made by skilled craftsmen called "kijishi". The characteristic of the Minamikiso rokuro-zaiku is that the grain of the wood produced by this rokuro-zaiku is brought out in its natural beauty. In 1980, Minamikiso rokuro-zaiku was designated as a national traditional craft.

MINO YAKI (MINO WARE)

CERAMIC - Tajimi/Toki/Mizunami/Kani, GIFU

Mino ceramics, or "Mino-yaki", is a generic name for all ceramics made in the Tônô region, Gifu Prefecture. Mino ceramics, which has a history of over 1300 years and a strong tradition, has evolved over time to reflect the tastes of the people and the trends of each era. As a result, Mino ceramics is not limited to one style, but has a wide variety of styles. Even today, Mino ceramics accounts for 60% of the total production of ceramics throughout Japan. From the middle of the Meiji era, everyday wares and a variety of vessels began to be produced throughout the region, and in order to reduce costs, a division of labor was established. On the other hand, many talented ceramists were trained in Mino, which is still an important center of activity for many ceramists today. Mino ceramics was designated a national "Traditional Craft" in 1978.